Childhood obesity is a stubborn problem to reverse in communities starved for cash. In a new five-year plan, Chicago health advocates put a priority on targeting funds and tracking results.

“We are not seeing significant improvement in disparities,” dietitian and food consultant Tracy A. Fox told the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children. The group outlined its policy agenda at a Sept. 16 meeting.

A decades-long rise in obesity rates has leveled off at 17 percent, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. “It’s a plateau at an insanely high rate,” Fox said.

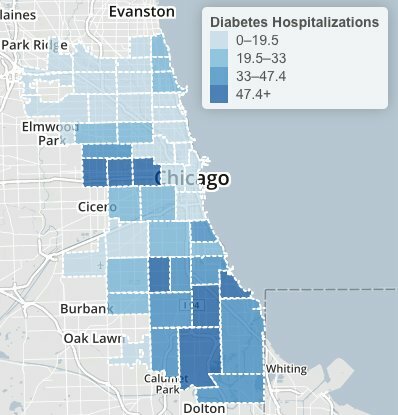

The overall trend also disguises rising obesity rates among minorities. “For African-Americans in particular we are seeing pretty significant increases. So I think we have our work cut out for us,” she said.

“As you discuss your policy agenda for this coalition, I would think about always viewing what you’re doing through the lens of how this would impact disparities,” Fox advised. “If you’re going into a middle- or upper- income school and you’re making significant changes, that’s really cool and that’s really nice. But are you then widening the gap between what’s happening in the city with African American and Latino kids and white middle- and upper-income kids?”

The group is refocusing priorities as both city and state lawmakers consider one of its initiatives, a tax on sugary beverages.

“There’s an argument to be made, if you’re just looking to lower consumption, then where that money goes is maybe not as important as just raising the price of soda,” said executive director Adam Becker. Still, the group is pushing for proceeds to benefit public health instead of sweetening general revenues.

“The feasibility is not really a question anymore,” Becker said. “It’s more the political will.”

The City Council health committee in September considered a penny-an-ounce tax. But its chair, Ald. George Cardenas (12th Ward) has not committed to advancing the plan. A state tax on distributors gained Chicago and suburban sponsors but has not advanced in the Legislature.

“It shows momentum,” said Elissa Bassler, chief executive of the Illinois Public Health Institute. “It’s being seriously considered as a source of revenue to improve health and invest those revenues into health initiatives.”

As new policies gain traction, data analysis has emerged as a priority. “Just because a bill got signed into an act or an ordinance passed doesn’t necessarily mean the things you intended to have happen are indeed happening,” Becker said. “A lot of the real hard work comes when you have to then monitor where things are going.”

For example, Illinois requires schools to take body-mass measurements, but the consortium wants the data tracked to identify areas in need. In the latest review of Chicago Public Schools data, roughly half of students were overweight or obese in 11 of Chicago’s 77 community areas.

The coalition of public-health advocates wants to build on recent legislative victories. Childcare centers in Illinois now must meet standards on physical activity, nutrition, screen time and breastfeeding. The group seeks to extend the licensing requirements to child-care family homes.

Less sugar and fat are now required in subsidized school food programs, along with more vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean protein and low-fat dairy. The consortium wants to maintain the higher standards and expand a federal summer nutrition program, which reaches only 15 percent of eligible children in Illinois.

“We work a lot in school breakfast,” said Bob Dolgan, executive director of the Greater Chicago Food Depository. “And it’s surprising even in low-income school districts how few administrators think about the fact that they have children coming to school without a meal and not eating until lunchtime. How can they possibly concentrate and excel in school without a meal?”

The group also pledges to spread novel ideas such as doubled food stamp benefits at farmers’ markets, a loan pool to build grocery stores in food deserts, and a “baby friendly” designation for hospitals that support breastfeeding.

And it advocates plans to encourage recreation and make streets safer. “In the first several iterations of the transportation bill, there’s been a big shift of more money for walking and bicycling,” said Melody Geracy, deputy executive director of the Active Transportation Alliance. “It is still a microscopic grain of sand in terms of the overall transportation budget. Still, it’s a target” for cost-cutters, Geracy said.

The group’s five-year plan retools an agenda set at a 2010 conference of local advocates. Policy-focused members shared a draft this spring with the group’s executive committee. Becker said national advisors provided details on policy specifics. Lurie Children’s Hospital, where the consortium is based, checked for conflicts with its own positions.

“You all as a city are probably farther ahead than a lot of even big urban cities in terms of really trying to come together with a unified agenda,” Fox told the group.

The policy document says political support is “particularly threatened” for federal health supports such as Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health. The CDC program pays for health screening in Chicago minority communities.

She advised local advocates to talk up their victories. “The more evidence base you have, the better,” she noted, but success stories from the front lines are more likely to engage lawmakers.

Local policy strategists suggested that closing gaps in outcomes will require wider access to preventive care. “Reducing disparities isn’t the same as creating equity,” said Joseph Harrington, regional health officer for the Illinois Department of Public Health.