This is the first of a five-part series exploring how to develop civic technology with, not for communities. Each entry in this series reviews a different mode, or strategy, of civic engagement in civic tech along with common tactics for implementation that have been effectively utilized in the field by a variety of practitioners. The modes were identified based on research I conducted with Smart Chicago as part of the Knight Community Information Challenge. Read more about the criteria here.

MODE: Utilize existing social infrastructure

Social infrastructure refers to the ecosystem of relationships and formal and informal organizations in a community. Structures can be physical (such as institutions with actual storefronts, like a daycare center) or purely relational (like a parents’ meet-up group), and most are organized by some element of place (neighborhood, school district, city district, city, etc).

Although structures can be shared across communities (a daycare center can draw people from multiple neighborhoods), the particular social infrastructure of a community is always unique. One may rely heavily on the daycare center while another nearby may prefer informal babysitting co-ops or church programs. Outsiders aren’t likely to spot these more informal and relational structures, making it hard to discover the structures that really matter in a given social context.

To address this knowledge gap, literally meet people where they are — work with (or as part of) the social structures that you can identify that already play a role in the context you hope to affect and work together to customize the best community approach.

Here are three specific tactics, each with concrete examples of real-world use, that can help you think about using existing social infrastructure in civic tech:

Pay for Organizing Capacity in Existing Community Structures

Whether you’re trying to catalyze new tech activity or create general opportunities for communal self-direction in tech, investing money where a community is already investing social capital is a one method of working with existing social infrastructure.

Investing in the capacity of organizers to expand their work and seek opportunities to leverage technology is a direct way of ensuring that tech is both is situated in a communal context and won’t be made an afterthought to competing priorities.

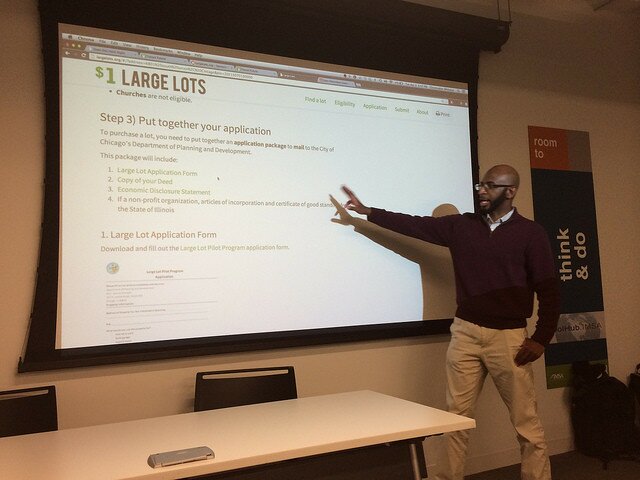

The Chicago Large Lots program has gained a lot attention for its tech platform LargeLots.org, which lets residents of particular neighborhoods purchase city-owned vacant lots for $1. This online platform originated not within Chicago’s civic hacking community but thanks to the coordination of various neighborhood associations and community groups at the helm of the policy response to this issue. As the policy developed in coordination with the City, these groups eventually leveraged social connections to craft civic tech to help execute the policy.

These social connections existed in part due to a previous investment in organizing capacity from the federally-funded Broadband Technology Opportunities Program (BTOP). In Chicago, some BTOP money was directed towards helping local organizations hire tech organizers and digital literacy instructors to “expand digital education and training for individuals, families, and businesses”.

Demond Drummer, former tech organizer at Teamwork Englewood, presents on LargeLots.org. Photo by Chris Whitaker.

One of those organizations was Teamwork Englewood, a community organization that would later play a role in the creation of the Large Lots Program. As part of the larger Program, Teamwork Englewood was able to steward the creation of LargeLots.org because, thanks to BTOP, Teamwork had existing paid staff whose responsibility it was to both invest in local digital skills and seek context-relevant opportunities to leverage those skills for neighborhood change.

Paid capacity can express itself in a far more localized ways, too. For example, the student-run Hidden Valley Nature Lab, which enables teachers to modify their curricula for place-based learning using QR codes, is the product of general paid support (at both the teacher and student-level) for digital educational programming within the communal social infrastructure that is New Fairfield High School, a public school in Western Connecticut.

Partner with Hyperlocal Groups with Intersecting Interests

Digital Stewards settling up the Red Hook Wifi network. Image via DigitalStewards.org.

Red Hook Wifi, a community-designed and stewarded wireless Internet network in Red Hook, Brooklyn, New York, is the product of a layered series of partnerships:

- A national organization (the Open Technology Institute (OTI), with expertise in community wireless networks)

- A hyperlocal organization (the Red Hook Initiative (RHI), a community center devoted to social justice and restoration of local public life through youth-led approaches)

- A variety of educational, residential, and local business relationships that not only utilize the network, but help expand the capacity available to keep the network alive through another RHI program, the Digital Stewards.

This deep meshing of missions, skills, and structures enabled the national organization (OTI) to support hyperlocal work in a way that genuinely allowed the local organization (RHI) to not only drive, but ultimately (literally) steward the ongoing success of both the wifi network and the social infrastructure needed to keep the network relevant and present within the community.

Offer Context-Sensitive Incentives for Participation

Although most of the examples above focus on organizational relationships, to catalyze the participation of individuals, explore the use of specific incentives.

For example, the Civic User Testing Group (CUTGroup) is a model of user experience testing run by the Smart Chicago Collaborative that enables “regular residents” to explore and critique so-called civic apps. To date, most participants are given a $20 VISA gift card for their engagement, although Smart Chicago is exploring the use of more contextually relevant awards, such as money for groceries for testing apps related to food access.

Sometimes getting to play specific role in the activity can be its own currency. DiscoTechs (short for “Discovering Technology”) are an open event format for teaching and sharing digital skills in a communal context) and operate utilizing social capital incentives. Although some DiscoTechs cater to specialized skills, many give neighbors, peers, and local organizations the chance to demonstrate a variety of personal technical expertise (such as photography, digital storytelling, music-making, coding, fabrication, you name it) and gain new community credibility alongside new contracts and other opportunities in the process.

DiscoTech stations can range from mapping and coding how-tos to digital storytelling to…Scrabble., each offering unique incentives to participate for both teachers and attendees. Photo by Maureen McCann.

***

Up next: Mode #2: Utilizing Existing Tech Skills and Infrastructure.

**Disclaimer: I receive funding for my research from both the Smart Chicago Collaborative as well as the Open Technology Institute at New America. However, any projects covered by these organizations in the course of my research have been subjected to the same evaluation criteria that all projects in the Experimental Modes Initiative are subject to. More details about these criteria and my methodology can be found here.

Design for America is an award-winning nationwide network of interdisciplinary student teams and community members using design to create local and social impact. Design for America teaches human centered design to young adults and collaborating community partners through extra-curricular, university based, student led design studios to look locally, create fervently and act fearlessly.

Design for America is an award-winning nationwide network of interdisciplinary student teams and community members using design to create local and social impact. Design for America teaches human centered design to young adults and collaborating community partners through extra-curricular, university based, student led design studios to look locally, create fervently and act fearlessly. This morning, Wednesday, March 11, 2015, at 10AM, I will be chairing a meeting of the Digital Divide Elimination Advisory Committee in the Director’s Conference Room of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO) in Suite 3-400 of the State of Illinois Building at 100 W. Randolph Street, Chicago, IL 60601. If you want to dial in, you can do so at 1-888-494-4032 / Access #: 2828938287.

This morning, Wednesday, March 11, 2015, at 10AM, I will be chairing a meeting of the Digital Divide Elimination Advisory Committee in the Director’s Conference Room of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO) in Suite 3-400 of the State of Illinois Building at 100 W. Randolph Street, Chicago, IL 60601. If you want to dial in, you can do so at 1-888-494-4032 / Access #: 2828938287. On Monday, Smart Chicago Executive Director Dan O’Neil went on WBEZ’s Tech Shift to talk about what the Homan Square story says about open data in Chicago.

On Monday, Smart Chicago Executive Director Dan O’Neil went on WBEZ’s Tech Shift to talk about what the Homan Square story says about open data in Chicago. At OpenGovChicago this year, we’ve been focusing on learning about and helping grassroots groups that interact with official government functions. This time the focus was on Chicago Public Schools and Local School Councils. Local School Councils were first created in 1988 from the Chicago School Reform Act. Local School council members are elected and receive training from Chicago Public Schools. Local School Councils are elected boards that serve at each school. Contract and charter schools do not have Local School Councils. Local School Councils (LSC) are responsible for three main duties:

At OpenGovChicago this year, we’ve been focusing on learning about and helping grassroots groups that interact with official government functions. This time the focus was on Chicago Public Schools and Local School Councils. Local School Councils were first created in 1988 from the Chicago School Reform Act. Local School council members are elected and receive training from Chicago Public Schools. Local School Councils are elected boards that serve at each school. Contract and charter schools do not have Local School Councils. Local School Councils (LSC) are responsible for three main duties: Using this criteria, I analyzed dozens of “civic technology” projects, mostly, but not exclusively within the US. I disregarded whether or not the projects or creators identified with “civic tech,” looking instead at whether or not the “tech” in question was created to serve public good. (Our interest, after all, is to explore the “civic” in “civic tech.”)

Using this criteria, I analyzed dozens of “civic technology” projects, mostly, but not exclusively within the US. I disregarded whether or not the projects or creators identified with “civic tech,” looking instead at whether or not the “tech” in question was created to serve public good. (Our interest, after all, is to explore the “civic” in “civic tech.”)