On April 4th, as part of the Experimental Modes project, we gathered together 30 technology practitioners in a one-day convening to discuss the strategies they use to make civic tech—though very few attendees would call it such.

Artists, journalists, developers, moms, community organizers, students, entrepreneurs (and often, some combination of the above), the practitioners in the room represented diverse parts of the civic ecosystem and the words we each used to talk about the work that we do reflected that.

Below, we’ve rounded up thoughts from each participant in answer to the question:

Before you came into this room did you think of your work as “civic tech”? If you didn’t, how would you describe your work?

The answers provide an important window into the limits and potentials of “civic technology”: who feels invited into this latest iteration of the “tech for good” space and who doesn’t (or who rejects it) and why.

(What follows are a slightly cleaned up version of the live notes taken during our conversations. You can read the original, unedited documentation of this conversation here.)

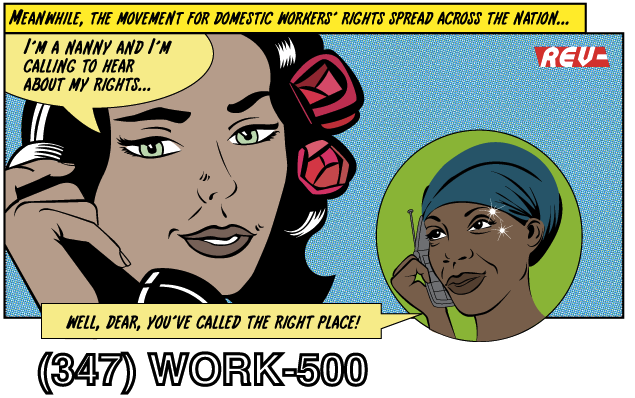

Marisa Jahn (The NannyVan App): At first we called our work public art, but then we identified as civic tech because the White House called us.

Maegan Ortiz (Mobile Voices): I identified the work as civic tech because I was told that what I do is civic tech, though with the populations I work with, civic engagement has a particular meaning.

Geoff Hing (Chicago Tribune): If you owned the language, what language would you use to describe your work?

Maegan Ortiz: Great question — for me, we have meetings and make media. We’re putting ourselves out there in different ways.

Marisa Jahn: We code switch a lot. Communications, civic media.

Asiaha Butler (Large Lots Program): We’re open to being as “googleicious” as possible. What we do is community.

Geoff Hing: I call my work journalism/journalistic.

Greta Byrum (Open Technology Institute): “Training”.

Stefanie Milovic (Hidden Valley Nature Lab): I’d call it “civic tech”. The21 only people who get involved are people who are looking to learn.

Jeremy Hay (EPANow): I’d call it civic tech depending on the grant. Otherwise, “Community journalism”

Tiana Epps-Johnson (Center for Technology and Civic Life): Skills training and civic tech.

Naheem Morris (Red Hook Digital Stewards): Training.

Laura Walker McDonald (Social Impact Lab): For FrontlineSMS, I’d say m-gov, m-health, etc. Digital Diplomacy. Civic tech. But the term I like the most is “inclusive technology”, which baffles people because we made it up.

Robert Smith (Red Hook Digital Stewards): Training, skill building. Not tied into government, so “civic” may not apply. Community building. “Independent”. “Tied in to building the Red Hook community”.

Jennifer Brandel (Curious Nation): Well, now I’m going to start using “civic tech” for grants. Usually, though, we call our work “public-powered journalism”. Sometimes I think about our work in terms of psychogeography: “a whole toy box full of playful, inventive strategies for exploring cities… just about anything that takes pedestrians off their predictable paths and jolts them into a new awareness of the urban landscape”. (“A New Way of Walking”)

Demond Drummer (Large Lots Program): I only started using “civic tech” about 6 months ago. Usually I refer to the work of tech organizers as “digital literacy” and “digital leadership”, in the mode of the literacy trainings from the Mississippi Freedom Movement. Now I think of what I do as the “full stack of civic tech”.

Josh Kalov (Smart Chicago Collaborative): Open data and website stuff. “Everything I do is civic tech though I hate the term”.

Anca Matioc (AbreLatAm): I work with a foundation in Chile, similar to Sunlight Foundation. Building platforms to inform people about voting, political issues. I hate the term “civic tech”. It’s missing “a lot of what you guys [in the room] have”, missing the communities part, the engaging grassroots part. People from civic tech need more of that. Impressed with R.A.G.E. (Asiaha’s organization), their structure and constituent funding (and therefore their constituent accountability). Maybe that’s why organizations like R.A.G.E. don’t immediately identify as civic tech, because they don’t have to adopt language for funders.

Allan Gomez (The Prometheus Radio Project): I don’t use the term civic tech, but our work does fall under it. I’d call it “participatory democracy”. Having a voice (through radio) is a civic ambition. Electoral politics is not the full range of civic participation. What about non-citizens? People who don’t vote can be politically engaged in a really deep way, more so than people who only vote and that’s it.

Sanjay Jolly (The Prometheus Radio Project): Our work falls into civic technology frames – and that can be important, useful. For a long time Prometheus was a “media justice organization” (to tell funders “what we are”). Now nobody call themselves media justice anymore. What makes sense to people is to say that “we’re building a radio station so people can have a voice in their community”.

Whitney May (Center for Technology and Civic Life): Our work fits pretty squarely with civic tech language because we’re building tools for government. But it’s also skills training, so I’d also call it “technically civic”.

Sabrina Raaf (School of Art and Design at University of Illinois at Chicago): I’d call it open source culture. Documenting new tech. Teaching new tech. Bridging between academia and maker culture (two cultures that are biased against each other). “Sharing knowledge”, documenting knowledge, workshopping knowledge.

Daniel O’Neil (Smart Chicago Collaborative): I work in civic tech, and I find the people in civic tech deeply boring.

Sonja Marziano (Civic User Testing Group, Smart Chicago Collaborative): “Civic” is a really important word to what I do every day.

Maritza Bandera (On The Table, Chicago Community Trust): I never thought of what I did as “civic tech” before. Conversation. Community-building. Organizing.

Adam Horowitz (US Department of Arts & Culture): Social imagination, cultural organizing, building connective tissue in social fabric.

Danielle Coates-Connor (GoBoston2030): Something I haven’t seen in the civic tech space is about the interior condition of leaders…the visionary elements.

Diana Nucera (Allied Media Projects): I think of civic tech more as product than process. It’s hard to hear people wanting to take the term and use it because it takes several processes to create a product that can scale to the size of civic tech—beyond a neighborhood, something that can cover a whole area. Taking over the term civic tech de-legitimizes the history of social organizing. When we use blanket terms we have to start from scratch. What I do is “media-based organizing”. The work is heavy in process, not products. The products are civic tech. So, I discourage people from using words civic technology to get grants, and so on. We actually need more diversity in processes—that’s what can make civic tech valuable.

Laurenellen McCann (Smart Chicago Collaborative): This is something I’ve been struggling with as I’ve been exploring the modes of civic engagement in civic tech—it’s a study of processes people use to create civic tech…but I’ve been wrestling with whether and how things that identify as “civic tech” count.

Diana Nucera: What you’ve shown us is that community organizing, media making, public art, all have a place within civic tech. And what I find helpful is to understand how people are approaching it: “Civic tech” or “Community tech”.

Similarly, The NannyVan’s Domestic Worker Alliance App was also the product of a longer-tail two-way educational initiative. The app, a phone hotline structured around a fictional, educational show, was developed

Similarly, The NannyVan’s Domestic Worker Alliance App was also the product of a longer-tail two-way educational initiative. The app, a phone hotline structured around a fictional, educational show, was developed