Public health information is anonymous. In the day of the data breach, identity theft and wearable health trackers, data scientists have procedures in place to keep it that way.

“Health information presents a huge risk,” says security researcher Larry Ponemon. In a report for the Medical Identity Fraud Alliance, he estimates that 2.3 million Americans have been victims of medical identity theft.

The biggest danger to consumers comes from others using their insurance or other identification to run up medical bills. “You want to take whatever steps you can to protect yourself,” Ponemon says. “In the hands of a criminal, that could be really valuable.”

Data provided to researchers, such as the statistics in the Chicago Health Atlas, are stripped of private data beforehand. What’s left is information designed to compare groups, not individuals.

The goal in data handling is to make sure identities can’t be guessed.

“There is a difference between privacy and security issues,” says Brad Malin, vice chair of biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. Malin advised on safe handling of atlas data.

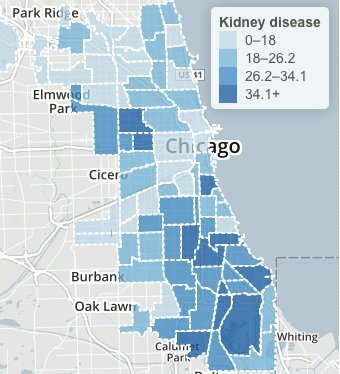

“The power of opening up the data is giving people some quick intuition about issues that deserve study,” Malin says. “You can take diabetes and look for a correlation where there are food deserts.”

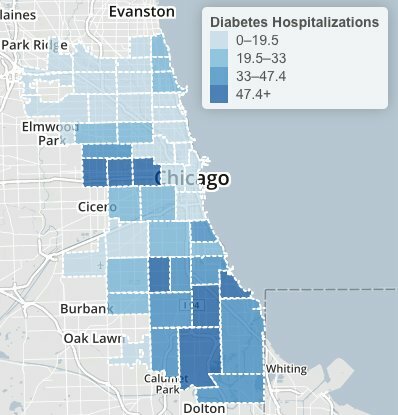

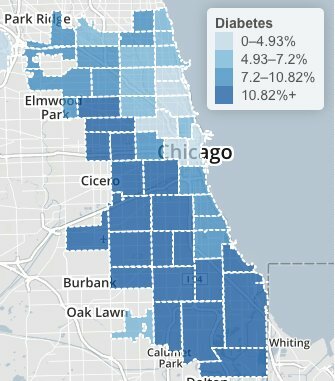

Chicago Health Atlas: Adult diabetes rates, 2006 through 2012.

The Chicago Health Atlas maps shows high diabetes levels across a large swath of Chicago’s South and West sides. Hospital records suggest the highest prevalence in North Lawndale’s 60623 ZIP code, with the most hospitalizations. An animation shows hospitalizations year by year, with the highest recent rate in Calumet Heights’ 60619 area.

Before giving statistics to outsiders, hospitals remove names and other identifiers, such as birthdays or treatment dates. “You may see residents of one neighborhood with an increased chance of having that diagnosis,” Malin says, “but this system will not allow you to drill down on any factors. There’s no individual-level data.

Health workers also withhold unique cases, where a patient might be identified from a combination of sources and guesswork. “We did not investigate rare disorders in the Health Atlas,” Malin says. “You never disclose information on less than five people.”

This can be a sticky issue for agencies that tackle public health emergencies. In a privacy panel at last fall’s Chicago School of Data conference, City of Chicago informatics project manager Matthew Roberts noted that information like date, sex, county and age might be enough to reveal the identity of a West Nile virus victim.

“If you take a look at the obituaries in a small county,” Roberts said, “for any of those given days where the date of death was mentioned, you could pretty quickly figure out who was the 84-year-old male who had died from disease x.”

Federal guidelines recommend making some data more general to protect privacy. In a case like a West Nile virus death, health workers will giving an age range, or a wider area such as northern Illinois.

Data mining also figures into how much information is released. Health workers consider whether identities can be pieced together from multiple sources. That’s a real danger in data breaches: Hackers mine social media profiles to work up enough information to make a false credit application or tax refund filing.

To study medical outcomes by neighborhood, several years of data might be combined to cut the chances that individuals might be re-identified.

“It’s safety in numbers,” Malin says. “You put your faith in that a certain number of individuals are enough to protect the anonymity of everyone in the group. As you get more specific, the risks go up.“

Still, there are dangers to being profiled as a group. Chicago community activists fought for years against insurers identifying whole neighborhoods as bad risks. Battles against home insurance redlining ultimately were resolved in court.

Health care reform bans insures from denying coverage for pre-existing conditions. However, the Affordable Care still allows higher rates by location. The rules require broad areas, no smaller than an entire county. But higher costs still may keep some insurers out of urban areas.

“What are the risks? It’s not quite clear,” Malin says. “In this situation the dangers are group-based. The regulations are defined with respect to individuals. “

Citizens give up bits of their privacy every day to stores or websites tracking their habits, with few complaints if it keeps prices low. But we treat medical care as a public good. We accept that some small piece of our health interactions are for the greater good, whether it’s teaching interns on hospital rounds or stopping infectious disease outbreaks. Our medical care is confidential, but not exactly secret.

“For 150 years, there’s been the expectation that medical information will be used for the public benefit,” Malin says. “In any teaching hospital, or any for-profit hospital for that matter, the information can be reused, unless you decide to be an anonymous patron who pays out of pocket.

“At the end of the day it’s a risk-utility tradeoff,” Malin says. “Unless somebody is actually harmed, they’re not going to see this as a risky situation. These are questions on the table as we move into a data-based society.”