A data-sharing network of 10 Chicago hospitals could make medical research more reliable and less expensive. It’s a big-data project that keeps patients records locked up, but lets researchers search for trends.

An $8.75 million grant will fund the three-year launch of the Chicago Area Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Network. Awarded July 21, the contract taps money set aside in the Affordable Care Act for medical research.

Terry Mazany, The Chicago Community Trust

“What’s unique about CAPriCORN is that it brings together these 10 institutions that historically have been competitors, or at least disinterested in each other,” says Terry Mazany, chief executive of The Chicago Community Trust and the project’s principal investigator. (The trust is also a Smart Chicago funder.)

“This brings them together in a very formal organization across the entire region,” Mazany says, “with a patient population of upwards of 5 million patients potentially available for research, and in particular a patient population that is very diverse.”

The Chicago network and clinical networks in 10 other regions will allow health advocates to monitor even rare conditions and prove how well current treatments work.

Their first test will be Duke University’s nationwide study to prove whether taking children’s aspirin to prevent a heart attack is as effective as an adult dose, which carries potential side effects. Researchers in Chicago and five other cities will study 20,000 at-risk heart patients, a large sample size that allows fine-tuned analysis.

Richard Kennedy, Loyola University Chicago

“They contacted us and said, you’ve got the numbers that we need, would you be able to participate?” says Richard Kennedy, vice provost for research and graduate studies at the Loyola University Chicago health sciences division in Maywood. “We had a significant number of patients that would fit nicely in the cohort.” Kennedy and Frances Weaver are Loyola’s head researchers for the data network.

Hospitals now are collaborating on how to conduct the trial and manage the data. Other studies will track obese patients after bariatric surgery and children on antibiotics to treat immune disorders. Mazany sees Chicago hospitals as active participants. “When the national level is looking at need and expertise in an area, we have a far broader and deeper bench than any of the other systems,” he says. “That’s a real strength.”

In a $7 million startup phase, CAPriCORN built out a system to connect the medical centers without exposing patient information. The next phase explores its real-world uses, as well as a funding model that puts patients’ interests first.

The aspirin study “is going to answer a question of great clinical concern,” Kennedy says, “but the importance is truly we’re testing the infrastructure we’ve been building for the past 18 months. All right, you’ve put together what seems to be a very impressive informatics system with all the security we would want for our patients. Now let’s see if it works.”

Privacy starts with keeping personal identifiers off the network. Researchers query data in a small, separate access layer, with names and addresses reduced to a cryptographic hash. “We’re currently having it validated by a security firm that’s one of the top in the region to make sure it protects subjects,” Kennedy says.

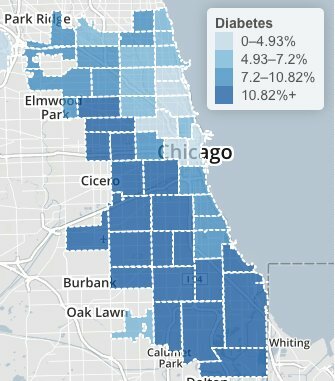

A novel algorithm links the anonymous patients’ records across all hospitals, giving public health researchers a more reliable count of how common their condition is and where to find hot spots. “You have the ability to look for rare diseases and aggregate an adequate sample size to do statistically significant studies,” Mazany says.

“There’s a next step in some of the research designs,” he adds. Instead of just counting how many patients share a condition, studies that pass an ethics review will reach out to them.

“Let’s say you’re looking at exploring treatments for sickle cell, and you’re specifically looking at teenagers as a population,” he explains. “Then you can do a query to identify the total population and where they’re distributed among institutions.”

Hospitals then can ask patients to join clinical trials that will log treatment details. “It still protects patient privacy but is able to more efficiently identify candidates for the research study,” Mazany says.

Researchers see the network as low-cost way to recruit trial subjects. “Instead of tens of thousands of dollars per participant, then it’s dollars per participant,” Mazany says. “You leverage the efficiency of large data systems so each researcher doesn’t independently have to enroll institutions.

“What makes this in someone’s interest? Lowering the cost of research, speeding up research, creating greater effectiveness. Those three standards are part of a health system that’s learning and evolving rapidly.”

The focus likely will improve data handling as well. “One interesting byproduct could be if there is unevenness across institutions that may become apparent,” Mazany says.

Research on the network will be subject to more thorough advance review. “It’s patient centered,” Loyola’s Kennedy says. “It includes a lot of patient input into the design of the study, the importance of the study to the subjects, the patients, the community.”

Like other clinical trials, research must pass muster with an institutional review board. Feedback also comes from a doctor-patient advisory panel that includes advocates for treating asthma, arthritis and other diseases.

“There’s also a pastor’s group on the South Side that’s very active,” Mazany says. The advisory group “totals about 30 people — it’s a pretty large group.”

The extra review should put important research on a fast track, and prime doctors and patients to follow its recommendations.

“Oftentimes research truly answers medical questions for the people that ran it, yet the results don’t get distributed and implemented as well as we would like,” Kennedy says. “We hope that by engaging the community and the patients – and the clinicians who are taking care of those patients – the results will be implemented much more quickly, because they will be designed in part by input from these subjects.”

The aspirin study also will look into the benefits of mobile health devices. A University of California-San Francisco team will give some participants apps to send reminders and record activity. In Chicago, Kennedy says investigators are considering how they might manage frequent readings from blood sugar monitors in a diabetes trial.

The network is “more open and accessible for that type of data collection,” Mazany says. “Who knows where that will lead as far as the efficacy of the research?”

Hospitals will have to consider a long-term funding model after federal funding runs out in 2018. “We’ve been contacted by an industry sponsor, who would very much like to think that there was a Chicago network they could access without working individually with the 10 institutions,” Kennedy says “That’s going to take some time to create that kind of trust.”

Mazany wants to make sure patient advocates can propose research on the network, but they’ll need to be thoroughly vetted. “They’ll come up with their own queries, but there won’t be an open-data hack night,” he says. “There are just too many privacy and security concerns with these types of data. But in a sense, the hack night would be communities and patients identifying questions that could interrogate data sets through the mechanism of the queries.”

The network has no data portal, but researchers will be encouraged to find ways to show their work outside of medical journals. That may include websites such as Smart Chicago’s Chicago Health Atlas, a past collaborator with hospital networks.

“The Health Atlas is an example of a good partner both on the front end of identifying important trends in the data that can help to frame priorities, and then on the back end as a distribution system for communications outward,” Mazany says. “I look for the Health Atlas to be a very valuable partner, but none of this has been formalized.”

The big-data approach also might spread beyond hospitals. “I don’t know how that’s going to play out,” Mazany says. The network already includes community health centers that store electronic health records centrally. He envisions opening up the network to more health providers.

“That line of thinking is an exciting frontier,” Mazany says. “Right now everybody is up to their necks in alligators draining the swamp. The analogy with Walt Disney envisioning Disney World and Florida in the midst of the swamp I think is appropriate here. We have a vision and are laying the infrastructure to have arise a Magic Kingdom.”