In the beginning, government data was stored on pieces of parchment and kept in bureau. Only the government employees knew where all the documents were thus giving us the word: bureaucrat.

Today, government is different. Now cities across the country are putting government data on data portals that can be accessed by anyone and everyone. Not to long ago, if governments put an PDF online it was considered open government. Now it’s a punchline.

Having vast stores of government data is great, but to make this data useful – powerful – takes a different type of approach. The next step in the open data movement will be about participatory data.

Systems that talk back

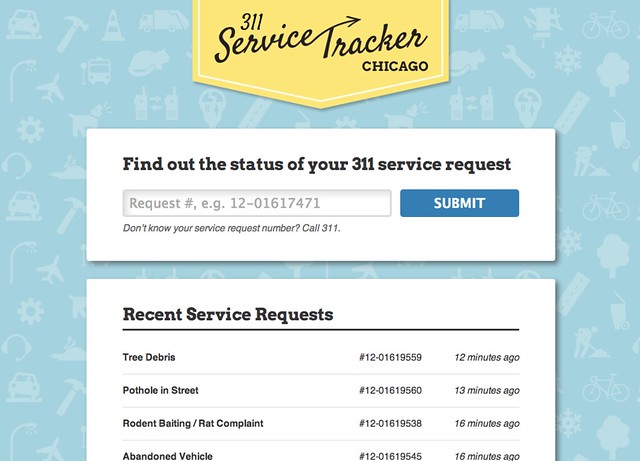

One of the great advantages behind Chicago’s 311 ServiceTracker is that when you submit something to the system, the system has the capacity to talk back giving you a tracking number and an option to get email updates about your request. What also happens is that as soon as you enter your request, the data get automatically uploaded into the city’s data portal giving other 311 apps like SeeClickFix and access to the information as well.

Given the fact that it used to be that no information was sent back when you reported something to 311, but it’s not participatory. There’s no room for feedback in the current system. That may change soon as the City of Chicago is putting out a bid for a new 311 system that “provide a holistic, transformative solution to help the City of Chicago provide world-class resident relationship management services.”

Participatory Legislative Apps

We already see a number of apps that allow user to actively participate using legislative data.

At the Federal level, apps like PopVox allow users to find and track legislation that’s making it’s way through Congress. The app then allows users to vote if they approve or disapprove of a particular bill. You can then send explain your reasoning in a message that will be sent to all of your elected officials. The app makes it easier for residents to send feedback on legislation by creating a user interface that cuts through the somewhat difficult process of keeping tabs on legislation.

At the state level, New York’s OpenLegislation site allows users to search for state legislation and provide commentary on each resolution.

At the local level, apps like Councilmatic allows users to post comments on city legislation – but these comments aren’t mailed or sent to alderman the same way PopVox does. The interaction only works if the alderman are also using Councilmatic to receive feedback.

In the end, legislative data tends to lend itself community discussion – that’s the way the legislative process is supposed to work. But what about data that’s not generated by elected officials?

Crowdsourced Data

Chicago has hardwired several datasets into their computer systems, meaning that this data is automatically updated as the city does the people’s business.

But city governments can’t be everywhere at once. There are a number of apps that are designed to gather information from residents to better understand what’s going on their cities.

In Gary, the city partnered with the University of Chicago and LocalData to collect information on the state of buildings in Gary, IN. LocalData is also being used in Chicago, Houston, and Detroit by both city governments and non-profit organizations.

Another method the City of Chicago has been using to crowdsource data has been to put several of their datasets on GitHub and accept pull requests on that data. (A pull request is when one developer makes a change to a code repository and asks the original owner to merge the new changes into the original repository.) An example of this is bikers adding private bike rack locations to the city’s own bike rack dataset.

Going from crowdsourced to participatory

Shareabouts is a mapping platform by OpenPlans that gives city the ability to collect resident input on city infrastructure. Chicago’s Divvy Bikeshare program is using the tool to collect resident feedback on where the new Divvy stations should go. The app allows users to comment on suggested locations and share the discussion on social media.

But perhaps the most unique participatory app has been piloted by the City of South Bend, Indiana. CityVoice is a Code for America fellowship project designed to get resident feedback on abandoned buildings in South Bend.

CityVoice takes the abandoned building dataset and tags each one with a property call-in number. Residents then call the number and leave a voicemail commenting about how they feel about the property. Do they want the property to be demolished? Do they want it left alone so somebody can buy it? And what reasons? What’s the context?

The CityVoice provides a great platform for residents to participate in the process of deciding what buildings get demolished or left standing. Because the input is done by phone, residents not comfortable with the internet can still leave feedback. You can watch the South Bend Fellows talk about their app here:

While the civic innovation community has created a number of apps that make it easy to understand government data, the next phase should be taking this data and using the data to facilitate dialog between decision makers and residents.

There are a number of areas that are prime targets for this kind of app including public safety and participatory budgeting. At the basic level, government data is all about the people and we look forward to seeing a more participatory approach to this data.